What does it mean for plants when you have an early fall freeze?

The first week of October this past year, here in Colorado’s high desert, an early fall severe freeze got me thinking about plant dormancy – and whether and how we can manipulate the plant’s dormancy through practical approaches.

It’s the second fall in which we did not anticipate early freezes, but got them anyway. Climatic changes are affecting the way we’ll be gardening and farming in the future.

This year, we went from 75-degree daytime temperature to 15-degree daytime temperature overnight. And the cold lingered for days. There was no slow transition or incremental transition to cold temperatures, which gives plants and fruit trees time to slowly transition to a dormant state.

I reached out to Colorado State University’s Tri-River Extension and asked them to look under microscope to assess the damage.

How our lavender plants were impacted by an early fall freeze

Overall, most of our lavender plants were good at the 3-4″ mark into the cut stem sample.

My initial findings were that species, year of the planting and field placement, and surrounding protection resulted in some differences.

The younger the plant, the more damage further into the plant took place. Older plants were more protected. Lavandula x. intermedia cultivars (Lavandins) had less plant tissue damage than L. angustifolias.

On the stems, I found up to 3” to 4” inches of damaged dead plant tissue, particularly amongst the L. angustofolias – auxiliary buds (which grow from the axil of a leaf) and terminal buds (at the tip of the shoots) were dead.

Propagating after a freeze

We typically start our herb and lavender propagation in late October. Due to the tissue damage on the plants from the freeze, it had me thinking if there are ways we will have to pivot our approach (seems like the new norm since the COVID pandemic!) in order to keep our plants surviving the winters.

Farming and gardening makes you a keen observer of nature.

I find myself most often thinking of how I can control, if at all, the outcome of a plant’s success. All I can do is observe, make adjustments and try new approaches, and try to understand some basic scientific concepts.

It helps to approach solutions by understanding plant dormancy even at its basic level. I will be looking at lavender more closely when thinking about ways to prevent cold damage on semi-woody herbaceous plants.

What is plant dormancy?

Dormancy can be triggered by shorter days and less daylight, by cooler temperatures, or both, depending on the plant. Dormancy can also be triggered by extreme heat or drought, which causes the plant to enter a state of dormancy until more favorable growing conditions arrive.

The state of endo-dormancy, the deep state of dormancy, lavender plants (like many other semi-woody herbaceous plants) are cold hardy. As long as the trees, bushes or vines are in endo-dormancy, they have the ability to acclimate to cold weather; this is cold hardiness.

As long as temperatures are below freezing, the plants are ready for really cold temperatures. Maximum cold hardiness occurs when plants have been subject to subfreezing temperatures for several days or more.

But what happens if the plants do not have time to acclimate? What can you do prevent premature damage to the plant?

Woody plants need to go dormant in order to survive winter’s conditions: cold temperatures and lack of sunlight. Otherwise, the tree would die from a lack of water resources due to frost, or not produce enough energy to sustain itself. In order to survive through the winter, trees must “fall asleep”. They’re still alive, but do not allocate energy to growth, and they perform very few functions.

The type of dormancy depends on the climate the trees or shrubs grows in, but most follow a general path.

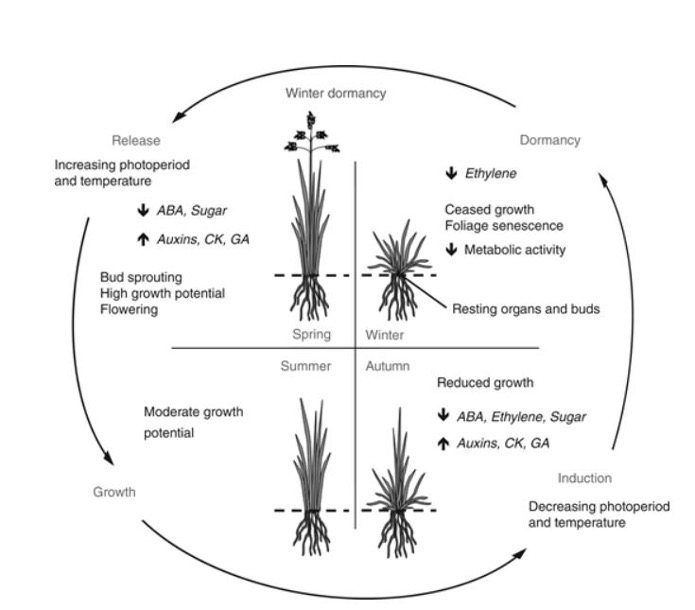

Diagram of the annual induction and release cycle of winter dormancy in a herbaceous perennial species and the associated variations in phytohormone and molecule concentrations. ABA, abscisic acid; CK, cytokinin; GA, gibberellin.

How does dormancy work?

First, trees and perennial shrubs need to know that it’s time to go dormant. Temperature and day length act as signals, just as a bedtime ritual signals you it is time to go to bed, such as brushing your teeth or turning off your reading light tells your mind it is time to shut down. Cooler temperatures help the plant to enter into a state of dormancy.

However, it is unreliable due to irregular seasonal temperatures. Day length, or more specifically, the length of darkness regulates growth hormones in plants. Short summer nights stimulate growth in most plants. Longer periods of darkness, created by the earth’s axis tilting away from the sun during winter1, signal a cessation of growth.

However, it is unreliable due to irregular seasonal temperatures. Day length, or more specifically, the length of darkness regulates growth hormones in plants. Short summer nights stimulate growth in most plants. Longer periods of darkness, created by the earth’s axis tilting away from the sun during winter1, signal a cessation of growth.

Three stages of dormancy follow: pre-dormancy, true-dormancy and post-dormancy.

During true-dormancy, trees and woody perennials need to develop cold hardiness, meaning they can survive the coldest of possible winter temperatures. Some plants will keep the water in their cells in a liquid state, rather than frozen solid, by increasing the number of solutes like minerals and hormones which lowers the freezing point. This is called supercooling.

Other plants will push water out of the cells and into the spaces in between, where it can safely freeze without damaging the cell, which is called intracellular dehydration. This allows plants to survive at colder temperatures than if they supercooled, but they may suffer from dehydration. These mechanisms prevent frost cracking, when water in a tree for example freezes and expands, cracking the tree in half. The tree may survive for a while after frost cracking but will be less stable.

In regions where plants express winter dormancy, the predominant stresses include freezing temperatures, soil heaving and ice encasement. Freezing temperatures induce plant dehydration, which disrupts the plant’s water status and causes potentially lethal osmotic and oxidative stress.

Soil heaving, the uplift of soil caused by repetitive freezing and thawing, can lead to the exposure of resting organs to cold temperatures with little or no insulation from the as well as damage to plant organs, i.e. roots, subjected to the physical stresses of soil heaving. Ice encasement can hinder or halt gas exchange, creating anaerobic conditions and injurious levels of CO2 These stresses can lead to tissue damage and potentially plant death.

Practical aspects: What does this all mean?

How can we manipulate negative outcomes of premature or extreme weather conditions in semi woody perennials?

Do we weather forecast and decide to cover and uncover plantings? Do we mulch around the plant base? Do we stop watering earlier?

Generally, the rule of watering before winter comes was to prevent plant dehydration. Here are some of the thoughts and possible approaches I may attempt. There are no straight-forward answers but experimentation and documentation is helpful. Track trends and try to minimize risk and minimize the plant damage.

- Perhaps with colder weather arriving earlier we need to shut off pre-season water by September (I will try this next season) or October, depending of your growing region. Plant cell damage may result if heavy watering occurs before a severe freeze and before plants have gone into endo- dormancy. This is what happened this last fall to my lavender plants

- Do not cover your plants with plastic touching the leaves. It is best to use woven frost protection blankets. In a mild freeze, one blanket or sheet will probably do for most plants. If it’s a hard freeze (below 30 degrees for any period of time) use a heavier weighted frost blanket or several layers of sheets. Remember to weight down fabric with rocks or something heavy on the edges so they do not blow off in the wind exposing roots and plants.

- If you are using floating row covers for plant protection, make sure plants are completely dormant. You do not want to break dormancy or prevent plant from going into endo-dormancy.

- As weather warms in late winter, check temperatures under cloth. If the temperatures are breaking dormancy prematurely you may consider uncovering for the rest of the season or uncovering and recovering once cold weather sets back in. This may be impractical for a large grower. This is where you have to document your success and failures over a period of time, this may help dictate if it is worth covering at all.

- It is important to remove all of your protective covering once temperatures are more or less above and consistently over 28 to 30 degrees. When the sun comes out and the temperature goes up, because it can be 32 degrees in the morning and heat up to 75 degrees and cook your plants.

- Observe which species and cultivars of lavender plants fair better in these extreme conditions. Perhaps the genes and genomic features of these plants are slowing their production early due to shorter days. I find this true with L. x. intermedias. Their new growth and budding are more affected with less daylight compared to that of L. angustifolias which could be actively growing in October and November.

- If you have a new planting you want to protect of being damaged by frost or freeze, apply a foliar spray of diluted seaweed extract (one teaspoon to the gallon of water) just before nightfall when frost is expected. Seaweed administered just before frost helps stop cold damage by increasing the sugar content in plant cells, thereby lowering the freezing point of the sap.

- It is best not to do any heavy pruning on freeze-damaged plants until late winter or early spring when you think all chance of hard freezes are over. I wait until early Spring just to make sure. Leaving damaged wood and leaves helps protect living part of the plant or shrub during the winter.

- Refresh your mulch layer before summer and before winter to ensure that the roots of your plants are protected from extreme heat and cold. I like to use raked fallen leaves, straw, spent lavender from distillation and de-budding of lavender stems and compost.

Coming next: Plant Dormancy, Part One

This spring, I will check in with you and we can see how the plants recovered from the early freeze. And a look at another kind of freeze damage. What happens when you receive a freeze in the late Spring after your lavender or woody and semi woody perennials have broken dormancy.

Sources:

University of Nebraska Lincoln Extension

Insights into Seasonal Dormancy of Perennial Herbaceous Forages

American Journal of Plant Sciences > Vol.8 No.11, October 2017

Insights into Seasonal Dormancy of Perennial Herbaceous Forages

Fay Waller

We have roughly 1000 lavender plants, and your information is very helpful. Oklahoma had the sudden transition from fall to winter last year. We are very grateful that we didn’t lose many plants, but some show the effects.

Our lavender adventure began in 2019, and we are learning through our many trials and enormous (not an exaggeration) errors.

Thank you for sharing your experience and knowledge!

Fay